The last three posts (see here, here, and here) have taken us through Python’s standard tkinter module from the basics to a simple windowed application with a text window for editing and the usual features for loading and saving text files.

I mentioned in the second post that I’d “implement a simple word-counter to replace the calculator parsing and execution code.” That’s what today’s short end-of-the-year post is about.

The last two posts explain the prefix calculator app and are prerequisites for this post. The discussion here assumes familiarity with the code from those posts (found in the ZIP file in last week’s post).

The goal is a class we can use instead of the Calculator class. The calculator app is designed to separate the user interface window from the backend that processes the user’s text. Recall that the Application class expects a Calculator class with the following methods and attributes:

tokens = parse_text(text) answer = execute(tokens) reset() results:list variables:dict opnames:list

Three methods, parse_text, execute, reset; and three attributes, results, variables, opnames. We looked at these in the last post; I won’t go into them here.

Rather than a calculator backend, this time we’ll implement a simple word counter that will tell us how many words the input text has. As a flourish, we’ll have it also tell us how many unique words there are.

To count words in text we first need to pick out the words from the whitespace and punctuation. We’ll do a first pass to convert punctuation to spaces and then use the str.split method to get a list of words.

Punctuation is tricky because of words such as “it’s” and “Fred’s” — do we treat the apostrophe as a valid word character and see contractions as distinct words or ignore possessives and contractions? If we convert the apostrophe to a space, we end up with occurrences of the single letter “s”. Complicating it is text using single-quotes (aka apostrophes) rather than double-quotes around text. Generally, we’d like to ignore the quotes in quoted text but treat possessives and contractions as distinct words.

Distinguishing those cases requires a more complicated parser than we’ll create here, so we’ll vanish the apostrophes to turn “it’s” and “Fred’s” to “its” and “Freds”. This compresses possessives and plurals, which is acceptable, but conflating “it’s” and “its” and other special grammatical cases is a price we pay for simplicity.

We’ll use the str.translate method to do the first pass of converting punctuation characters. [See Python String Translate for more on the str.translate method.] That method requires a translation map.

We’ll implement the map with a subclass of dict:

002| “””Transation filter.”””

003|

004| def __init__ (self, others=“”):

005| ”’New AlphaMap instance.”’

006| self[ord(‘.’)] = ‘.’

007| self[ord(‘_’)] = ‘_’

008| self[ord(“‘”)] = ”

009|

010| # A-Z and a-z…

011| for cx in range(26):

012| self[UCA+cx] = chr(UCA+cx)

013| self[LCA+cx] = chr(LCA+cx)

014|

015| # 0 through 9…

016| for cx in range(10):

017| self[DIG0+cx] = chr(DIG0+cx)

018|

019| # User-supplied characters…

020| for ch in others:

021| cx = ord(ch)

022| assert 0 <= cx < 256, ValueError(f’Illegal character: “{ch}“‘)

023| self[cx] = ch

024|

025| def __missing__ (self, cx):

026| “””All other characters map to spaces.”””

027| return ” “

028|

In the dunder init method (lines #4 to #23) explicitly populate the map with three punctuation characters, period, underbar, and apostrophe. We allow periods to ensure that floating-point numbers (such as “3.1415”) are seen as single words. Later, we’ll take steps to remove the periods. We include underbars because they are usually legitimate word characters (certainly in source code they are valid variable name characters).

Those two characters are translated to themselves. The apostrophe gets vanished, so contractions and possessives become single words (with no apostrophe).

Lines #10 to #13 install the alphabetical characters, upper- and lowercase. Lines #15 to #17 install the digits. Lastly, lines #19 to #23 install any user-supplied characters. In all three cases, these characters map to themselves. That is, they pass the filter untouched.

The dunder missing method (lines #25 to #27) is invoked for any character not found in the map — all the various punctuation, upper-ASCII characters, and control characters all get converted to spaces.

We can exercise this map class like this:

002|

003| Text = “””\

003| They’re $500/12, a #1 price. (10.4% off!)

003| Okay — it’s not without its problems.

003| And: We’re glad they were there.

003| “””

004|

005| if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

006| print(Text)

007| print()

008|

009| textfilter = AlphaMap(‘#$’)

010| cleantext = Text.translate(textfilter)

011| print(cleantext)

012| print()

013|

When run, this prints:

They're $500/12, a #1 price. (10.4% off!) Okay -- it's not without its problems. And: We're glad they were there. Theyre $500 12 a #1 price. 10.4 off Okay its not without its problems. And Were glad they were there.

The output is just words and spaces (including words with “$” or “#”). Note that apostrophes have been vanished, which collapses the contractions.

Now that we have a filter, let’s build a WordCounter “calculator” class.

Here’s the DOC text:

Word-Counter "Calculator".

A basic word-counter to replace the Calculator class.

This class replicates the attributes and methods of

the Calculator class but just counts words.

Attributes:

tokens list of words to count

variables unused but expected

constants unused but expected

results output string

Methods:

reset reset calculator

execute execute tokens

Class Methods:

opnames returns empty list

parse_text given text, return list of words

Note that we only implement the attributes and methods expected by Application.

Here’s the code:

002|

003| class WordCounter:

004| ”’Word-Counter “Calculator”.”’

005|

006| def __init__ (self, **kwargs):

007| ”’New instance.”’

008| self.tokens = []

009| self.variables = {}

010| self.constants = {}

011| self.results = [”]

012|

013| def __repr__ (self):

014| ”’Debug string.”’

015| return f’<{typename(self)} @{id(self):012x}>‘

016|

017| def __str__ (self):

018| ”’String version.”’

019| return ‘ ‘.join(self.tokens)

020|

021| def reset (self):

022| ”’Reset.”’

023| self.results = [”]

024|

025| def execute (self, words=”):

026| ”’Count the list of words.”’

027| self.tokens = words

028| self.unique = list(sorted(set(words)))

029| self.nw = len(self.tokens)

030| self.nu = len(self.unique)

031| self.nc = sum(len(word) for word in self.tokens)

032| text = f’{self.nw} words ({self.nu} unique), {self.nc} chars‘

033| self.results = [text]

034| return text

035|

036| @classmethod

037| def parse_text (cls, text):

038| ”’Break text into words. Remove all punctuation.”’

039| txt = text.translate(AlphaMap())

040| txt = txt.replace(‘. ‘, ‘ ‘)

041| if txt.endswith(‘.’): txt = txt[:–1]

042| txt = txt.lower()

043| return txt.split()

044|

045| @classmethod

046| def opnames (cls):

047| ”’No operators but an expected method.”’

048| return []

049|

The first part (lines #6 to #19) is very similar to the first part of the Calculator class from last week. The only notable difference is that constants isn’t populated, but results is (with an empty string).

The reset method (lines #21 to #23) is also similar but doesn’t need to reset variables. It puts the same default empty string into results (this ensures results always has an item so that results[0] is always valid).

Skipping to the end, the opnames class method (lines #45 to #48) just returns an empty list. There are no operators, but the method is expected by Application.

The parse_text class method (lines #36 to 43) is significantly different. It starts by passing the input text through AlphaMap to make the translations discussed above. Recall that we allowed periods. Line #40 replaces occurrences of “. ” (a period followed by a space) with a single space, which removes sentence-ending periods. The last sentence’s period doesn’t have a space after it, so line #41 checks for a final period and removes it if found.

Next the text is forced to lowercase (line #42). Lastly, the str.split method breaks it into a list of words, which are returned (line #43).

The execute method (lines #25 to #34) receives this list of words and binds tokens to them (to make them available after the method returns). It puts them in a set to create a sorted list of unique words (line #28). Then (lines #29 to #31) it counts words, unique words, and the number of characters used by the words (which excludes punctuation and whitespace, so is not a count of the characters in the original text).

Lastly, it creates a results string, which it returns (lines #32 to #34).

That’s all there is to it.

We can test this using the same text sample we used above:

002|

003| Text = “””\

003| They’re $500/12, a #1 price. (10.4% off!)

003| Okay — it’s not without its problems.

003| And: We’re glad they were there.

003| “””

004|

005| if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

006| print()

007| wc = WordCounter()

008|

009| # Break text into words…

010| words = wc.parse_text(Text)

011|

012| # Count the words…

013| result = wc.execute(words)

014|

015| print(result)

016| print()

017| print(wc.tokens)

018| print()

019| print(wc.unique)

020| print()

021|

When run, this prints:

20 words (18 unique), 77 chars ['theyre', '500', '12', 'a', '1', 'price', '10.4', 'off', 'okay', 'its', 'not', 'without', 'its', 'problems', 'and', 'were', 'glad', 'they', 'were', 'there'] ['1', '10.4', '12', '500', 'a', 'and', 'glad', 'its', 'not', 'off', 'okay', 'price', 'problems', 'there', 'they', 'theyre', 'were', 'without']

The first line is the official result. Then comes the list of words as created by parse_text. Last comes the alphabetized list of unique words.

Given the season, let’s test this again with the first two paragraphs from A Christmas Carol (1843), by Charles Dickens:

002|

003| Source = ”’\

003| Marley was dead: to begin with. There is no doubt

003| whatever about that. The register of his burial was

003| signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker,

003| and the chief mourner. Scrooge signed it: and

003| Scrooge’s name was good upon ’Change, for anything

003| he chose to put his hand to. Old Marley was as dead

003| as a door-nail.

003|

003| Mind! I don’t mean to say that I know, of my own

003| knowledge, what there is particularly dead about a

003| door-nail. I might have been inclined, myself, to

003| regard a coffin-nail as the deadest piece of

003| ironmongery in the trade. But the wisdom of our

003| ancestors is in the simile; and my unhallowed hands

003| shall not disturb it, or the Country’s done for. You

003| will therefore permit me to repeat, emphatically,

003| that Marley was as dead as a door-nail.

003| ”’

004|

005| if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

006| print()

007| wc = WordCounter()

008|

009| # Break text into words…

010| words = wc.parse_text(Source)

011|

012| # Count the words…

013| result = wc.execute(words)

014|

015| print(result)

016| print()

017| print(wc.tokens)

018| print()

019| print(wc.unique)

020| print()

021|

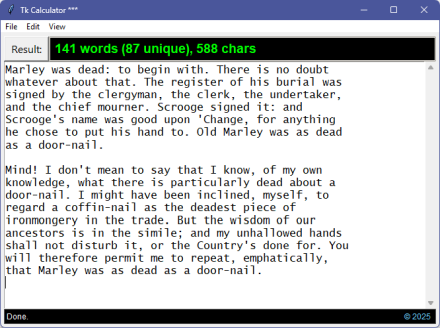

When run, this prints:

141 words (87 unique), 588 chars ['marley', 'was', 'dead', 'to', 'begin', 'with', 'there', 'is', 'no', 'doubt', 'whatever', 'about', 'that', 'the', 'register', 'of', 'his', 'burial', 'was', 'signed', 'by', 'the', 'clergyman', 'the', 'clerk', ... ... 'not', 'disturb', 'it', 'or', 'the', 'countrys', 'done', 'for', 'you', 'will', 'therefore', 'permit', 'me', 'to', 'repeat', 'emphatically', 'that', 'marley', 'was', 'as', 'dead', 'as', 'a', 'door', 'nail'] ['a', 'about', 'ancestors', 'and', 'anything', 'as', 'been', 'begin', 'burial', 'but', 'by', 'change', 'chief', 'chose', 'clergyman', 'clerk', 'coffin', 'countrys', 'dead', 'deadest', 'disturb', 'done', 'dont', ... ... 'say', 'scrooge', 'scrooges', 'shall', 'signed', 'simile', 'that', 'the', 'there', 'therefore', 'to', 'trade', 'undertaker', 'unhallowed', 'upon', 'was', 'what', 'whatever', 'will', 'wisdom', 'with', 'you']

Looks like it works okay. (Many lines removed to reduce size here.)

There are several ways we can arrange for Application to load different classes. A sophisticated way would be to load the class by name (or simple alias). We’ll use something more brute force and basic.

Here’s a new version of the first part of the Application class:

002| “””Tk Calculator Application class.”””

003|

004| def __init__ (self, file=”, mode=‘calc’):

005| ”’New Application instance.”’

006| self.filename = file

007| self.mode = mode

008| self.dirty = False

009| self.nofile = True

010|

011| # Load configuration…

012| self.config = Configuration()

013|

014| # Does the “calculation”…

015| if self.mode == ‘wc’:

016| self.calc = WordCounter()

017| else:

018| self.calc = Calculator()

019|

020| # Build the window…

021| self._create_widgets()

022| self._create_menubar()

023| # Show ourselves…

024| self.root.deiconify()

025| # Load’m if ya got’m…

026| if self.filename:

027| self.open_source_file()

028| # Set focus…

029| self.update_title()

030| self.update_status(f’Mode: {self.mode}‘, ‘#7fffaf’)

031| self.source.focus()

032|

033| …

034| …

035| …

036|

Lines #14 to #18 are the only change we need to make. The mode parameter to dunder init was in last time’s code but was left unused and unexplained. Now we see what its purpose is: it controls what backend class the app loads.

Currently, the only other class we know of is the WordCounter class we just created, so for demonstration purposes we’ll just use a simple if-else structure. For multiple classes, a match-case structure would be better.

The Calculator class is the default, so we explicitly test for a “wc” mode parameter and load WordCounter on a match.

We can launch our word counter explicitly with a bit of code like this:

002|

003| if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

004| print()

005| try:

006| app = Application(mode=‘wc’)

007| app.root.mainloop()

008|

009| except Exception as e:

010| print(f’Oops! {e}‘)

011|

012| else:

013| print(‘Success!’)

014|

015| finally:

016| print(‘Done.’)

017|

018| print()

019|

Or we can use a more general approach that uses a command line parameter:

002| from calc_wdw import Application

003|

004| if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

005| print()

006| mode = argv[1] if 1 < len(argv) else ‘calc’

007|

008| try:

009| app = Application(mode=mode)

010| app.root.mainloop()

011|

012| except Exception as e:

013| print(f’Oops! {e}‘)

014|

015| else:

016| print(‘Success!’)

017|

018| finally:

019| print(‘Done.’)

020|

021| print()

022|

Which launches the calculator by default but can be overridden with a command line parameter (in this case “wc”).

Either way:

And there we are. A dual-purpose script-based calculator and a word counter.

That’s it for the Calculator Application (at least for now). It’s also the end of the look into the tkinter module (at least for now). I may return to either or both down the road (or not).

What is certain is that this is the last post of 2025. I’ll be back in 2026 with more hard-core coding. In the meantime:

May you and yours have a wonderful, safe, and happy winter solstice season and a very happy new year!

Link: Zip file containing all code fragments used in this post.

∅

ATTENTION: The WordPress Reader strips the style information from posts, which can destroy certain important formatting elements. If you’re reading this in the Reader, I highly recommend (and urge) you to [A] stop using the Reader and [B] always read blog posts on their website.

This post is: Tk Calculator App Extra