I have a suite of simple CGI webapps that run on my localhost Apache webserver. Long ago they were Perl scripts. These days they are Python scripts. However, in some areas, Python can be a moving target. Case in point, the cgi module and the FieldStorage dictionary object.

The module was deprecated since Python 3.11 and removed in Python 3.13. Which I just installed on my new laptop. Which broke all my webapps. Which forced me to update them. Which went fine except for one app using multipart form data. This post documents the changes and some new code I wrote.

Prior to Python 3.13, handling CGI data was as simple as:

002|

003| if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

004| form = FieldStorage()

005| …

006|

Just import FieldStorage from the cgi module, then call it to get a dictionary of the submitted data. The keys are the field names, and the item values are the field values. A minor wrinkle is that when multiple fields share the same name, the field value is a list object of the multiple values.

For example, if the URL was something like this:

http://localhost/bin/myapp?x=21&y=42&z=63&a=foo&a=bar&a=moo

Then the form data would be:

- ‘x’: ’21’

- ‘y’: ’42’

- ‘z’: ’63’

- ‘a’: [‘foo’, ‘bar’, ‘moo’]

(Note that it’s all string data.) There is one more wrinkle — a not so minor one — that I’ll get to below. It has to do with handling cases when a file is sent to the webserver.

For the record, now that I’m running Python 3.13, running the code above prints:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "fragment.py", line 1, in

from cgi import FieldStorage

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'cgi'

Which is what all my webapps started doing.

For all but the app handling file data, the fix was fairly simple:

002| from os import environ

003| from urllib import parse

004|

005| if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

006| # GET data…

007| qs = environ.get(‘QUERY_STRING’, ”)

008| get_dict = parse.parse_qs(qs)

009|

010| # POST data…

011| post_len = int(environ.get(‘CONTENT_LENGTH’, 0))

012| post_txt = stdin.read(post_len)

013| post_dict = parse.parse_qs(post_txt)

014|

015| form = dict(**get_dict, **post_dict)

016| params = {}

017| for name in sorted(form):

018| value = form[name]

019| # If it’s a list of multiple items…

020| if 1 < len(value):

021| for ix,v in enumerate(value, start=1):

022| params[f’{name}–{ix}‘] = v

023| # Otherwise it’s just a name:value pair…

024| else:

025| params[name] = value[0]

026| …

027|

Rather than the FieldStorage function, we import the parse module from urllib.

CGI data can come from a GET request (parameters on the URL) or from a POST request (parameters in the stdin stream).

So, first the code obtains the QUERY_STRING text (if any) from the environment (line #7). It passes this to parse.parse_qs (line #8) and receives a dictionary object (get_dict). This contains the parameters from the URL.

Then (lines #11 and #12) the code obtains any text from stdin — this would be data submitted via a POST request. Line #13 calls parse_qs again with this text to get another dictionary object (post_dict).

Line #15 merges the two parse output dictionaries into a single dictionary (form).

One change is that the dictionary values parse_qs returns are always list object. If there was only one parameter with that name, there is just one object in the dictionary. (Previously, there were list objects only for multiple items with the same name.) All my webapp code expects single items, so the code in lines #17 to #25 goes through the items in form and copies them to params (which is what my code uses) as single items (line #25). It also expands lists with multiple items to params with names having “-1”, “-2”, and so on appended (line #22).

And that fixed my webapps. All but one.

That one was expecting file data in a POST request. As with all POST requests, the form data streams from stdin (note lines #11 and #12 in the code above). That isn’t the problem; the code above obviously solves that one.

The problem is, firstly, that my code previously accessed file data directly from the FieldStorage results for the associated parameter. I typically used a field named “fn” (filename) to post a file from my webform. Accessing the file was just a matter of:

002| …

003| for name in sorted(form):

004| …

005| # Load filename and file object into params…

006| if name == ‘fn’:

007| fobj = form[‘fn’]

008| params[‘fn’] = fobj.filename

009| params[‘fp’] = fobj.file

010| …

011| …

012|

013| # Use filename and file data…

014| fn = params[‘fn’]

015| bs = params[‘fp’].read()

016| …

017|

The code from line #3 to #9 was part of a loop similar to the one above that moves parameters from form to params. Line #6 gets the object FieldStorage returned. That object has a filename attribute (line #8) and a file attribute (line #9). The former is just a string, but the latter is a file object.

To use the file data (lines #13 to #15), the code accesses the ‘fn’ and ‘fp’ values in params. The file object had to be read to obtain the data (which is in bytes).

Without the parsing FieldStorage did, POST data in the stdin stream looks something like this:

------WebKitFormBoundaryFvgrhoe2FqQdLu4J Content-Disposition: form-data; name="userId" HT/50201 ------WebKitFormBoundaryFvgrhoe2FqQdLu4J Content-Disposition: form-data; name="sessId" EWZJGUQLEDTZEQXWOMERLWZY ------WebKitFormBoundaryFvgrhoe2FqQdLu4J Content-Disposition: form-data; name="ctrlId" 1768274923354599726 ------WebKitFormBoundaryFvgrhoe2FqQdLu4J Content-Disposition: form-data; name="fn"; filename="email_spam.py" Content-Type: text/x-python <<file-data>> ------WebKitFormBoundaryFvgrhoe2FqQdLu4J Content-Disposition: form-data; name="size" 1 ------WebKitFormBoundaryFvgrhoe2FqQdLu4J Content-Disposition: form-data; name="cols" 16 ------WebKitFormBoundaryFvgrhoe2FqQdLu4J Content-Disposition: form-data; name="enc" utf-8 ------WebKitFormBoundaryFvgrhoe2FqQdLu4J--

The multipart form data above contains seven parts — six for simple input strings and one for the file contents. Each part starts with a separator that begins with six hyphens. The text following the hyphens is unique to every submission. In CGI POST data, the separator is defined in the CONTENT_TYPE environment string.

The value for the above form data looked like this:

multipart/form-data; boundary=----WebKitFormBoundaryFvgrhoe2FqQdLu4J

Following the separator is one or more headers. There is always a Content-Disposition header that provides the name of the form field. In the part for the actual file data, the Content-Disposition header also contains the original filename. That part has a second header, the Content-Type header that describes the file content.

Following the header(s) is a blank line followed by the part’s data. For simple input, the data is just a single line of text. For the file, it’s the actual file bytes, which can be binary (if sending an image, for instance). The potential for binary data basically means all the data has to be processed as bytes.

I did look around for an existing module someone might have written for handling this and found one but couldn’t get it to work — it had unannounced dependencies I didn’t feel like chasing. After looking at the form data for a while, I decided it should be easy enough to code a parser.

What I’m posting here is the first version that I’ll use until it breaks or needs improvement somehow. It has worked on all the files I’ve tested it with, but I make no claims that it’ll handle everything. Take it as a starting point.

To handle parsing the headers, I made a separate class:

002|

003| class MimeHeader (tuple):

004| ”’\

004| MIME Header class. Parses text to a defined tuple.

004|

004| Expected text has the syntax:

004| <name>: <text> [; name=value [; …]]

004|

004| Created tuple is:

004| (name, text, fields)

004|

004| Properties:

004| name -field name

004| text -field text

004| fields -dictionary of name:value pairs

004|

004| Methods:

004| str(obj) -printable version

004| repr(obj) -debugging version

004| ”’

005| def __new__ (cls, text):

006| ”’New MimeHeader instance.”’

007|

008| # Split text into name and value parts…

009| parts = text.partition(‘: ‘)

010| if parts[1] != ‘: ‘:

011| ValueError(f’Invalid MIME Header (no “: “): “{text}“‘)

012|

013| # Split the value into fields…

014| subparts = parts[2].split(‘; ‘)

015| value = subparts[0]

016|

017| fields = {}

018| for subp in subparts[1:]:

019| # Split field into name and value…

020| key,val = subp.split(‘=’, maxsplit=1)

021| # Add field; remove any surrounding double-quotes…

022| fields[key] = val.strip(‘”‘)

023|

024| # Delegate creating new instance to tuple…

025| return super().__new__(cls, (parts[0], value, fields))

026|

027| @property

028| def name (self): return self[0]

029|

030| @property

031| def text (self): return self[1]

032|

033| @property

034| def fields (self): return self[2]

035|

036| def __str__ (self):

037| return f’{self.name}: {self.text}‘

038|

039| def __repr__ (self):

040| return f’<{type(self).__name__} @{id(self):08x}>‘

041|

042|

043| if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

044| hdr = MimeHeader(txt)

045| print(f’Header: {hdr} {hdr!r}‘)

046| print(f’Header Name: {hdr.name}‘)

047| print(f’Header Text: {hdr.text}‘)

048| print(‘Header Fields:’)

049| for nam,val in hdr.fields.items():

050| print(f’> {nam}: {val}‘)

051| print()

052|

Which should be pretty self-explanatory. It subclasses tuple, so MimeHeader objects are tuples with named fields plus nice debug and string representations. When run, this prints:

Header: Content-Disposition: form-data <MimeHeader @2388d272390> Header Name: Content-Disposition Header Text: form-data Header Fields: > name: fn > filename: foo.py

With that in hand, here’s the form data parser:

002|

003| EOL = ord(‘\n’)

004| CR = ord(‘\r’)

005| DASH = ord(‘-‘)

006|

007| def parse_multipart_form (content_type:str, byte_string:bytes) -> tuple:

008| ”’\

008| Parse Multipart Form Data.

008|

008| Arguments:

008| content_type -content header text

008| byte_string -form data bytes

008|

008| Returns:

008| tuple: (form, filename, filetype, filedata)

008|

008| Note: the last three field will be None if no file data.

008| ”’

009| form = {} # form data to be returned

010| parthdrs = {} # temp dictionary for part headers

011| content = [] # buffer for building file content

012| buf = [] # temp buff for building strings

013| state = ‘prefix’ # current state

014| boundary = None # part separator string

015|

016| # Parse the content-type header to get the multipart boundary…

017| ix = content_type.index(‘boundary=’) + len(‘boundary=’)

018| boundary = content_type[ix:].lstrip(‘-‘)

019|

020| # Iterate over the bytes of the data…

021| for bx in byte_string:

022|

023| if state == ‘prefix’:

024| # Accumulate dashes…

025| if bx == DASH:

026| buf.append(bx)

027| continue

028| # Not a dash; separator text begins…

029| if len(buf) < 6:

030| raise SyntaxError(f’Expected six hyphens, not {len(buf)}.‘)

031| # Add first separator character to buffer…

032| buf = [bx]

033| state = ‘sep’

034| continue

035|

036| if state == ‘sep’:

037| # End of separator…

038| if bx == EOL:

039| sep_str = ”.join(chr(b) for b in buf)

040| if not sep_str.startswith(boundary):

041| raise SyntaxError(f’Invalid Separator: “{sep_str}“‘)

042| buf = []

043| parthdrs = {}

044| state = ‘part.start’

045| continue

046| # Ignore CR characters…

047| if bx == CR:

048| continue

049| # Add separator character to buffer…

050| buf.append(bx)

051| continue

052|

053| if state == ‘part.start’:

054| # Blank line (instead of header text)…

055| if bx == EOL:

056| # End of part headers…

057| content = []

058| state = ‘part.data’

059| continue

060| # Ignore CR characters…

061| if bx == CR:

062| continue

063| # Add first part header character to buffer…

064| buf = [bx]

065| state = ‘part.hdr’

066| continue

067|

068| if state == ‘part.hdr’:

069| # Handle end of line…

070| if bx == EOL:

071| txt = ”.join(chr(b) for b in buf)

072| hdr = MimeHeader(txt)

073| parthdrs[hdr.name.lower()] = hdr

074| state = ‘part.start’

075| continue

076| # Ignore CR characters…

077| if bx == CR:

078| continue

079| # Add part header character to buffer…

080| buf.append(bx)

081| continue

082|

083| if state == ‘part.data’:

084| # A dash might mean a separator…

085| if bx == DASH:

086| buf = [bx]

087| state = ‘test.prefix’

088| continue

089| # Add content byte to buffer…

090| content.append(bx)

091| continue

092|

093| if state == ‘test.prefix’:

094| # Not a dash; start of separator…

095| if bx != DASH:

096| # Not a separator; add to content and resume…

097| if len(buf) != 6:

098| # Not a separator…

099| content.extend(buf)

100| content.append(bx)

101| state = ‘part.data’

102| continue

103| # Got 6 dashes; might be a separator…

104| buf = [bx]

105| state = ‘test.sep’

106| continue

107| # Add character to possible prefix string…

108| buf.append(bx)

109| continue

110|

111| if state == ‘test.sep’:

112| # End of line; test separator…

113| if bx == EOL:

114| txt = (”.join(chr(c) for c in buf)).strip()

115| if txt != boundary:

116| # Not a separator…

117| content.extend(buf)

118| content.append(bx)

119| state = ‘part.data’

120| continue

121| # It is a separator; get disposition header…

122| cdisp = parthdrs[‘content-disposition’]

123| name = cdisp.fields[‘name’]

124| # Add file content (bytes) to form (strip trailing CR-LF)…

125| form[name] = bytes(content[0:–2])

126| # Add the disposition header…

127| form[f’{name}.disp‘] = cdisp

128| # If content-type header provided…

129| if ‘content-type’ in parthdrs:

130| # Add to form…

131| form[f’{name}.type‘] = parthdrs[‘content-type’]

132| # Get ready for next part…

133| buf = []

134| parthdrs = {}

135| state = ‘part.start’

136| continue

137| # Add to separator string…

138| buf.append(bx)

139| continue

140|

141| # Extract the filename, filetype, and file data for convenience…

142| filedata, filename, filetype = None,None,None

143| for name in form:

144| if name == ‘fn’:

145| filedata = form[‘fn’]

146| filetype = form[‘fn.type’].text

147| filename = form[‘fn.disp’].fields[‘filename’]

148| if filetype.startswith(‘text’):

149| filedata = str(filedata, encoding=‘utf8’)

150| continue

151|

152| # Also convert simple fields from bytes to strings…

153| if ‘.’ not in name:

154| txt = form[name]

155| if isinstance(txt,bytes):

156| form[name] = str(txt, encoding=‘utf8’)

157|

158| form[‘fn.name’] = filename

159| return (form, filename, filetype, filedata)

160|

Kinda long, but state machines tend to that because each state requires handling code. It’s not as well commented as I’d like for publication, but the code isn’t doing anything especially complicated. It also lacks as much vertical whitespace as I usually use for clarity, but I wanted to keep each state’s code together.

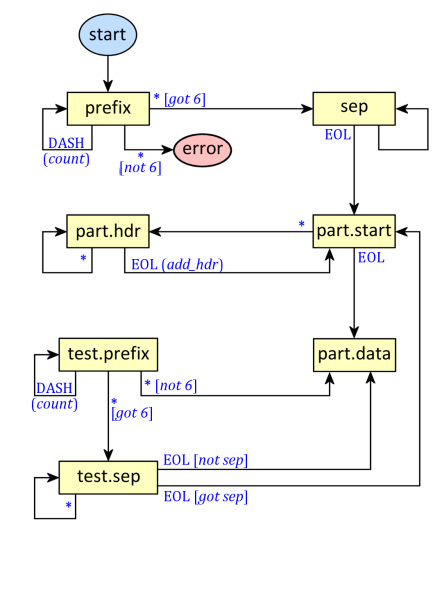

Here’s the state diagram for the state machine in the above code:

Text in blue is the condition that moves the state. Blue text in parentheses is an action; blue text in square brackets is an extended condition. For instance, any character other than a dash moves from the prefix state, which is counting dashes, to the sep (separator) state, which will gather the separator string. The “not 6” and “got 6” conditions check that the separator prefix is six dashes. Refer to the sample of multipart form text above to follow the state diagram and code.

We can exercise parse_multipart_form with this code:

002| from examples import parse_multipart_form

003|

004| FName = r’C:\Demo\Python\multipart-1.txt’

005| CType = r’multipart/form-data; boundary=—-WebK…Lu4J’

006|

007| def test_parser (file_name:str, content_type:str) -> tuple:

008| ”’Function to exercise Multipart parser.”’

009|

010| # Read multipart form data from file (binary mode)…

011| fp = open(file_name, mode=‘rb’)

012| try:

013| data = fp.read()

014| print(f’loaded: {file_name}‘)

015| print(f’bytes: {len(data)}‘)

016| print()

017| except:

018| raise

019| finally:

020| fp.close()

021|

022| # Parse the multipart form…

023| form,fname,ftype,fdata = parse_multipart_form(content_type, data)

024|

025| # List the form data…

026| for key in sorted(form):

027| val = form[key]

028|

029| if key == ‘fn’:

030| print(f’{key}: <filedata>‘)

031| continue

032|

033| if isinstance(val, str):

034| print(f’{key}: {val}‘)

035| continue

036|

037| print(f’{key}: {form[key].text}‘)

038|

039| print()

040|

041| return (form, fname, ftype, fdata)

042|

043| if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

044| print(f’autorun: {argv[0]}‘)

045|

046| file_name = argv[1] if 1 < len(argv) else FName

047| content_type = argv[2] if 2 < len(argv) else CType

048|

049| print()

050| form,fname,ftype,fdata = test_parser(file_name, content_type)

051| print()

052|

Note that in the source above I’ve truncated the content type global variable CType (line #5) to make the line fit this post. The actual code (as in the ZIP file) contains the full-length separator string. The code also expects a file containing form data. An example file is included in the ZIP file. Note that the content type string defining the separator must use the same separator string as the file data does.

When run, this prints:

autorun: fragment.py loaded: C:\Demo\Python\multipart-1.txt bytes: 3509 bd: le bd.disp: form-data cmd: Line# cmd.disp: form-data cols: 16 cols.disp: form-data ctrlId: 1768274923354599726 ctrlId.disp: form-data data: x data.disp: form-data dw: 2 dw.disp: form-data fn: fn.disp: form-data fn.name: email_spam.py fn.type: text/x-python nbrs: d nbrs.disp: form-data nw: 4 nw.disp: form-data sessId: EWZJGUQLEDTZEQXWOMERLWZY sessId.disp: form-data size: 1 size.disp: form-data userId: HT/50201 userId.disp: form-data

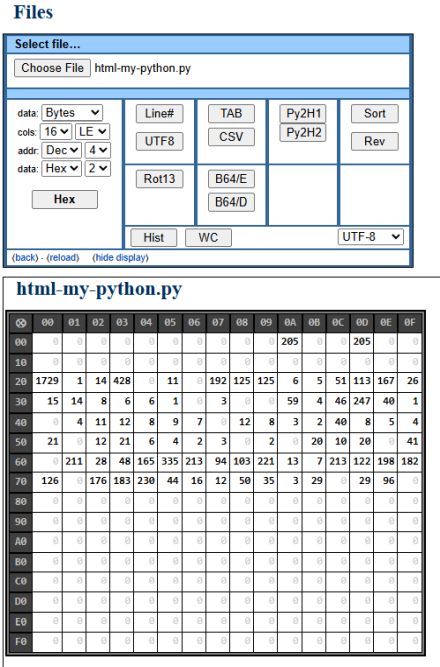

Not the prettiest output, but it suffices. Each field is from the webform I use to generate the input (and submit files for different kinds of processing). Here’s a screenshot of the UI I made:

It can produce hex dumps, line numbers, sorted output, and other processes including character histograms (output shown below webform) and word counts. It’s also capable of displaying CSV and TAB files as tables.

The Py2H buttons convert Python to colorized HTML (the two reflect different versions) Just a bunch of handy file utilities I use often enough to want simple apps to do them.

And I think that’s about all for this time.

Link: Zip file containing all code fragments used in this post.

∅

ATTENTION: The WordPress Reader strips the style information from posts, which can destroy certain important formatting elements. If you’re reading this in the Reader, I highly recommend (and urge) you to [A] stop using the Reader and [B] always read blog posts on their website.

This post is: Parsing Multipart Form Data