Tags

I’ve been working on an arbitrary-precision numeric class (in Python) that stores numbers in what amounts to base-256 — that is to say, in machine-native binary. It differs from the variable-length integers in Python by supporting fractions (and from Python’s Decimal number type by being binary).

It occurred to me I could implement multiplication with a lookup table rather than actually doing the math (at the CPU level, that may be what in fact is going on). So, I thought I’d compare the two implementations.

One might wonder what the point of an arbitrary-precision binary numeric type is given that Python’s Decimal type is more precise (and no doubt faster). But my goal lies beyond Python. I’m just using Python to develop an algorithm for calculating deep zooms in the Mandelbrot fractal. My idea is to use the many CPUs in a GPU to do parallel processing. Each pixel of a Mandelbrot rendering stands alone — there is no link to nearby pixels.

Which makes Mandelbrot renderings perfect for parallel processing. I want that processing to be as fast as possible, so I want to program as “close to the metal” as possible. Something like C or C++, if not assembly level. My ultimate goal fantasy is a “Mandelbrot Machine” capable of fairly deep real-time zooms.

[At this point, I’m not sure why something like that wouldn’t already exist. I doubt the idea is unique to me. Using a GPU is too obvious.]

The Mandelbrot equation is simple:

Both z and C are complex numbers. The latter, C, is the coordinate (aka pixel) being rendered, and is the same throughout the calculation (it is effectively a constant). The former, z, starts at zero. The calculated z is plugged back into the equation to generate another calculated z. This continues until either 2<|z| or an iteration maximum is reached.

The formula normally uses z² rather than z × z, but I used multiplication to show how the algorithm only requires multiplication and addition. The decimal point matters for a correct answer (and to align addition), but we can ignore it when comparing different multiplication techniques.

Addition isn’t possible without aligning the two operands, but multiplication is just their Cartesian product. The decimal point only matters for setting the result in the right range:

The actual digits of the answer don’t change. Since setting the result decimal point is a simple calculation done after the actual multiplying, we can ignore it here.

For a baseline, we’ll start with an algorithm that uses actual multiplication of the values involved:

002| ”’Multiply byte strings. Version 0. (No MulTable)”’

003| print(f’multiply0({bs1.hex(“.”)}, {bs2.hex(“.”)})‘)

004|

005| # Output buffer

006| buf = [0] * (len(bs1) + len(bs2))

007|

008| # Generate Cartesian products…

009| for ix1,b1 in enumerate(bs1):

010| for ix2,b2 in enumerate(bs2):

011| # Buffer index…

012| ix = ix1+ix2

013|

014| # Determine product and any carry…

015| carry,product = divmod(b1*b2, 256)

016| print(f’[{ix}]: {b1} * {b2} = {product}, {carry}‘)

017|

018| # Add to result buffer…

019| buf[ix] += product

020| buf[ix+1] += carry

021|

022| # Ripply carry buffer…

023| for ix in range(len(buf)):

024| carry,value = divmod(buf[ix], 256)

025| # Handle overflow…

026| if carry:

027| buf[ix] = value

028| buf[ix+1] += carry

029|

030| print(f’multiply0.exit: {buf}‘)

031| return bytes(buf)

032|

033|

034| if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

035| print()

036|

037| bs1 = bytes([255,255])

038| bs2 = bytes([255])

039| v1 = int.from_bytes(bs1, byteorder=‘little’)

040| v2 = int.from_bytes(bs2, byteorder=‘little’)

041|

042| res = multiply_bs_0(bs1, bs2)

043| val = int.from_bytes(res, byteorder=‘little’)

044| flg = ‘Ok!’ if (v1*v2)==val else str(v1*v2)

045| print()

046|

047| print(f’{list(bs1)} × {list(bs2)} = {res}‘)

048| print(f’{v1} × {v2} = {val} ({flg})‘)

049| print()

050|

The multiply_bs_0 function takes two parameters, both byte strings (type bytes), multiplies them, and returns the result, also a byte string.

Because we’re using bytes, the values range from 0 to 255. If we multiply the largest value, 255 × 255, we get 65,025 — which is way out of range, so we need to carry to the next byte.

A multiplication result can never have more digits than the sum of the number of digits in the operands. This is true regardless of base. For example, consider 99×99=9801. The nine digits are the maximum possible value for a digit, so the result is the largest possible result with two-digit operands. It has four digits.

A multiplication can have fewer digits in the result than the sum of the number of operand digits. For example, 01×01=0001 is a valid two-digit multiplication, but the result (absent leading zeros) has only one digit.

Bottom line, we calculate the size of the result buffer by summing the lengths of the two operands (line #6).

Lines #8 through #20 comprise a nested for loop that generates the Cartesian products and adds them to the buffer. Line #15 uses the built-in divmod function to handle possible overflow (which is added to the next buffer slot).

After adding the products, the buffer values may be too large, so lines #22 to #28 do a ripple carry to ensure all values are legal byte values.

Lines #34 through #49 exercise the function and flag a correct result in the display (or print what the value should have been).

When run, this prints:

multiply0(ff.ff, ff) [0]: 255 * 255 = 1, 254 [1]: 255 * 255 = 1, 254 multiply0.exit: [1, 255, 254] [255, 255] × [255] = b'\x01\xff\xfe' 65535 × 255 = 16711425 (Ok!)

Ok!

Now let’s try using a multiplication table:

002|

003| MulTable = [[itobs(a*b) for b in range(256)] for a in range(256)]

004|

The itobs (int to bytes) lambda function (line #1) converts an integer value to a pair of bytes.

MulTable is a nested list — essentially a 256×256 grid (65,536 values) — with all possible multiplication outcomes for two bytes. Obtaining an outcome just requires indexing the value:

val = MulTable[oper1][oper2]

Where oper1 and oper2 are each byte values to be multiplied. The result is always two bytes.

We can demonstrate MulTable:

002|

003| if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

004| print()

005|

006| #Show off some byte multiplications…

007| print(f’{MulTable[0x00][0x00] = }‘)

008| print(f’{MulTable[0x01][0x01] = }‘)

009| print(f’{MulTable[0x02][0x02] = }‘)

010| print(f’{MulTable[0x2a][0x2a] = }‘)

011| print(f’{MulTable[0x45][0x67] = }‘)

012| print(f’{MulTable[0x80][0x80] = }‘)

013| print(f’{MulTable[0xAB][0xCD] = }‘)

014| print(f’{MulTable[0xff][0xff] = }‘)

015| print(f’‘)

016|

Which when run prints:

MulTable[0x00][0x00] = b'\x00\x00' MulTable[0x01][0x01] = b'\x01\x00' MulTable[0x02][0x02] = b'\x04\x00' MulTable[0x2a][0x2a] = b'\xe4\x06' MulTable[0x45][0x67] = b'\xc3\x1b' MulTable[0x80][0x80] = b'\x00@' MulTable[0xAB][0xCD] = b'\xef\x88' MulTable[0xff][0xff] = b'\x01\xfe'

All correct answers, so the basic idea works.

Now let’s try using it to multiply byte strings. Here’s my first version:

002|

003| def multiply_bs_1 (bs1:bytes, bs2:bytes) -> bytes:

004| ”’Multiply byte strings. Version 1.”’

005| print(f’multiply1({bs1.hex(“.”)}, {bs2.hex(“.”)})‘)

006|

007| # Output buffer…

008| buf = [0] * (len(bs1) + len(bs2))

009|

010| # Generate Cartesian products…

011| for ix1,b1 in enumerate(bs1):

012| for ix2,b2 in enumerate(bs2):

013| # Buffer index…

014| ix = ix1+ix2

015|

016| # Get b1*b2 product…

017| res = MulTable[b1][b2]

018| print(f’[{ix}]: {b1} * {b2} = {res}‘)

019|

020| # Add LSB…

021| buf[ix] += res[0]

022| # Add MSB…

023| buf[ix+1] += res[1]

024|

025| # Ripply carry buffer…

026| for ix in range(len(buf)):

027| carry,value = divmod(buf[ix], 256)

028| # Handle overflow…

029| if carry:

030| buf[ix] = value

031| buf[ix+1] += carry

032|

033| # Return buffer…

034| print(f’multiply1.exit: {buf}‘)

035| return bytes(buf)

036|

037|

038| if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

039| print()

040|

041| bs1 = bytes([255,255])

042| bs2 = bytes([255])

043| v1 = int.from_bytes(bs1, byteorder=‘little’)

044| v2 = int.from_bytes(bs2, byteorder=‘little’)

045|

046| res = multiply_bs_1(bs1, bs2)

047| val = int.from_bytes(res, byteorder=‘little’)

048| flg = ‘Ok!’ if (v1*v2)==val else str(v1*v2)

049| print()

050|

051| print(f’{list(bs1)} × {list(bs2)} = {res}‘)

052| print(f’{v1} × {v2} = {val} ({flg})‘)

053| print()

054|

The main difference between this version 1 and version 0 above is in lines #16 to #23 where we get the MulTable result and add its two bytes to the result buffer. As we did in the previous version, we need a ripple carry loop (lines #25 to #31) to ensure we return valid byte values.

The exercise code from line #38 to #53 is the same as used before, and when run, this has (nearly) the same output:

multiply1(ff.ff, ff) [0]: 255 * 255 = b'\x01\xfe' [1]: 255 * 255 = b'\x01\xfe' multiply1.exit: [1, 255, 254] [255, 255] × [255] = b'\x01\xff\xfe' 65535 × 255 = 16711425 (Ok!)

So far, so good.

I had the idea that, rather than using a list buffer, I could use a dict with the buffer index as the key. I was curious which method of indexing was faster. Is it better to constantly update a list or selectively update dictionary entries?

That led to version 2:

002|

003| def multiply_bs_2 (bs1:bytes, bs2:bytes) -> bytes:

004| ”’Multiply byte strings. Version 2.”’

005| print(f’multiply2({bs1.hex(“.”)}, {bs2.hex(“.”)})‘)

006|

007| # Accumulator…

008| terms = {ix:0 for ix in range(len(bs1) + len(bs2))}

009|

010| # Generate Cartesian products…

011| for ix1,b1 in enumerate(bs1):

012| for ix2,b2 in enumerate(bs2):

013| # Buffer index…

014| ix = ix1+ix2

015|

016| # Get product and add to terms…

017| res = MulTable[b1][b2]

018| terms [ix] += res[0]

019| terms [ix+1] += res[1]

020|

021| answer = [terms[ix] for ix in sorted(terms.keys())]

022| print(f’multiply2.products[{b1},{b2}]: {answer}‘)

023|

024| # Ripple carry the terms…

025| for ix in sorted(terms.keys()):

026| carry,value = divmod(terms[ix], 256)

027| if 0 < carry:

028| terms[ix] = value

029| terms[ix+1] += carry

030|

031| # Return the terms…

032| answer = [terms[ix] for ix in sorted(terms.keys())]

033| print(f’multiply2.exit: {answer}‘)

034| return bytes(answer)

035|

036|

037| if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

038| print()

039|

040| bs1 = bytes([255,255])

041| bs2 = bytes([255])

042| v1 = int.from_bytes(bs1, byteorder=‘little’)

043| v2 = int.from_bytes(bs2, byteorder=‘little’)

044|

045| res = multiply_bs_2(bs1, bs2)

046| val = int.from_bytes(res, byteorder=‘little’)

047| flg = ‘Ok!’ if (v1*v2)==val else str(v1*v2)

048| print()

049|

050| print(f’{list(bs1)} × {list(bs2)} = {res}‘)

051| print(f’{v1} × {v2} = {val} ({flg})‘)

052| print()

053|

This is similar to version 1, but the list used as a result buffer is replaced with a dict (line #8). At the end, we generate a list from the dictionary (line #32).

The nested for loop (lines #10 to #22) works differently here. It looks up the product result in MulTable (line #17) and adds the values to the indexed dictionary entries (lines #18 and #19).

The ripple carry (lines #24 to #29) is essentially the same as before but happens to be indexing dictionary entries rather than list slots.

Lines #37 to #52 exercise the code as done with previous versions. When run, this prints:

multiply2(ff.ff, ff) multiply2.products[255,255]: [1, 254, 0] multiply2.products[255,255]: [1, 255, 254] multiply2.exit: [1, 255, 254] [255, 255] × [255] = b'\x01\xff\xfe' 65535 × 255 = 16711425 (Ok!)

Ok! This version works, too.

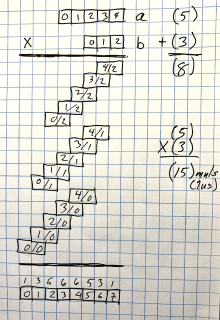

Thinking about the two-byte MulTable results, it occurred to me that while the buffer indexes are revisited multiple times, the pair of indexes for the operands are unique. Consider the following multiplication:

The number pairs (4/2, 3/2, etc.) are the unique pairs — ix1 and ix2 in the code above, rather than their sum, ix, which indexes the result buffer. Obviously, that sum repeats, but the pairs do not. As you see in the diagram above, each intermediate result from MulTable has a unique pair indexing it, no repeats.

Note in the upper right the sum of the number of digits in the operands: 5+3=8. The result can have no more than eight digits. The middle right multiplication of those same numbers gives the number of multiplications (or lookups) — the count of the Cartesian products.

Given the unique index pairs for those products, I though why not just stash them in a dictionary — keyed by the index pair — and add them up (and do carry) as a second step. That led to this version:

002|

003| def multiply_bs_3 (bs1:bytes, bs2:bytes) -> bytes:

004| ”’Multiply byte strings. Version 2.”’

005| print(f’multiply3({bs1.hex(“.”)}, {bs2.hex(“.”)})‘)

006|

007| # Output buffer…

008| buf = [0] * (len(bs1) + len(bs2))

009|

010| # Accumulator…

011| terms = {}

012|

013| # Generate Cartesian products…

014| for ix1,b1 in enumerate(bs1):

015| for ix2,b2 in enumerate(bs2):

016| # Terms index…

017| key = (ix1,ix2)

018|

019| # Add to terms…

020| terms[key] = MulTable[b1][b2]

021| print(f’multiply3.product[{b1},{b2}]: {terms[key]}‘)

022|

023| # Sum the terms into the result buffer…

024| for key in sorted(terms.keys()):

025| ix = sum(key)

026| res = terms[key]

027| buf[ix] += res[0]

028| buf[ix+1] += res[1]

029|

030| # Ripply carry buffer…

031| for ix in range(len(buf)):

032| carry,value = divmod(buf[ix], 256)

033| # Handle overflow…

034| if carry:

035| buf[ix] = value

036| buf[ix+1] += carry

037|

038| # Return buffer…

039| print(f’multiply3.exit: {buf}‘)

040| return bytes(buf)

041|

042|

043| if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

044| print()

045|

046| bs1 = bytes([255,255])

047| bs2 = bytes([255])

048| v1 = int.from_bytes(bs1, byteorder=‘little’)

049| v2 = int.from_bytes(bs2, byteorder=‘little’)

050|

051| res = multiply_bs_3(bs1, bs2)

052| val = int.from_bytes(res, byteorder=‘little’)

053| flg = ‘Ok!’ if (v1*v2)==val else str(v1*v2)

054| print()

055|

056| print(f’{list(bs1)} × {list(bs2)} = {res}‘)

057| print(f’{v1} × {v2} = {val} ({flg})‘)

058| print()

059|

Which has noticeable differences from previous versions. Firstly, the nested Cartesian product for loop (lines #13 to #21) now just stores the MulTable result in the terms dictionary under a tuple key of (ix1,ix2). As these keys are unique, there’s no need to initialize terms or sum values into existing keys.

Secondly, a new for loop (lines #23 to #28) does a one-pass sum of terms into the result buffer.

The ripple carry loop in lines #30 to #36 is what we’ve seen before. Likewise, the exercising code from lines #43 to #58.

When run, this prints:

multiply3(ff.ff, ff) multiply3.product[255,255]: b'\x01\xfe' multiply3.product[255,255]: b'\x01\xfe' multiply3.exit: [1, 255, 254] [255, 255] × [255] = b'\x01\xff\xfe' 65535 × 255 = 16711425 (Ok!)

Ok!

Now that we have four different versions, let’s time them with a long-ish multiplication:

002| from time import perf_counter_ns

003| import examples as eg

004|

005| if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

006| times = int(argv[2]) if 2 < len(argv) else 1000

007|

008| # Operand strings…

009| s1 = argv[2] if 2 < len(argv) else ‘255, … ,255’

010| s2 = argv[3] if 3 < len(argv) else ‘255, … ,255’

011|

012| # Convert string to integer values…

013| ds1 = [int(d, base=0) for d in s1.split(‘,’)]

014| ds2 = [int(d, base=0) for d in s2.split(‘,’)]

015|

016| # Make the byte strings for multiplying…

017| bs1 = bytes(ds1)

018| bs2 = bytes(ds2)

019| v1 = int.from_bytes(bs1, byteorder=‘little’)

020| v2 = int.from_bytes(bs2, byteorder=‘little’)

021| answer = v1 * v2

022| print(f’1 = {v1:,}‘)

023| print(f’2 = {v2:,}‘)

024| print(f’A = {answer:,}‘)

025| print()

026|

027| # Version 1…

028| t0 = perf_counter_ns()

029| for _ in range(times):

030| res = eg.multiply_bs_0(bs1, bs2)

031| t1 = perf_counter_ns()

032| val = int.from_bytes(res, byteorder=‘little’)

033| print(f’version 0: {(t1–t0)/1000000:.3f} ms‘)

034| print(‘Ok!’ if val==answer else f’OOPS: {val:,}‘)

035|

036| # Version 1…

037| t0 = perf_counter_ns()

038| for _ in range(times):

039| res = eg.multiply_bs_1(bs1, bs2)

040| t1 = perf_counter_ns()

041| val = int.from_bytes(res, byteorder=‘little’)

042| print(f’version 1: {(t1–t0)/1000000:.3f} ms‘)

043| print(‘Ok!’ if val==answer else f’OOPS: {val:,}‘)

044|

045| # Version 2…

046| t0 = perf_counter_ns()

047| for _ in range(times):

048| res = eg.multiply_bs_2(bs1, bs2)

049| t1 = perf_counter_ns()

050| val = int.from_bytes(res, byteorder=‘little’)

051| print(f’version 2: {(t1–t0)/1000000:.3f} ms‘)

052| print(‘Ok!’ if val==answer else f’OOPS: {val:,}‘)

053|

054| # Version 3…

055| t0 = perf_counter_ns()

056| for _ in range(times):

057| res = eg.multiply_bs_3(bs1, bs2)

058| t1 = perf_counter_ns()

059| val = int.from_bytes(res, byteorder=‘little’)

060| print(f’version 3: {(t1–t0)/1000000:.3f} ms‘)

061| print(‘Ok!’ if val==answer else f’OOPS: {val:,}‘)

062|

This calls each of the four functions a bunch of times (1000 by default — line #6). The input strings on lines #9 and #10 have been shortened to fit this post. Each actually contains 12 occurrences of 255 — the ellipses symbolize the missing 10.

Note how, as in the previous examples, we validate the returned multiplication result against an integer result done on line #21.

When run, this prints:

1 = 79,228,162,514,264,337,593,543,950,335 2 = 79,228,162,514,264,337,593,543,950,335 A = 6,277,101,735,386, ... ,946,612,225 version 0: 19.739 ms Ok! version 1: 19.414 ms Ok! version 2: 24.090 ms Ok! version 3: 33.035 ms Ok!

The result surprised me a little.

Using multiplication to generate Cartesian products is just as fast as using a lookup table and adding values to a list. Using a dict is noticeably slower, and version using tuple indexes is even slower.

It would be interesting to convert those first two versions to C++ or assembly and see how they compare without any Python overhead.

[Come to think of it, I did just write a CPU simulator and assembler (in Python). A Python CPU simulator would run much slower than a real CPU, but it should allow comparisons between routines. Hmmm… 🤔]

Link: Zip file containing all code fragments used in this post.

∅

ATTENTION: The WordPress Reader strips the style information from posts, which can destroy certain important formatting elements. If you’re reading this in the Reader, I highly recommend (and urge) you to [A] stop using the Reader and [B] always read blog posts on their website.

This post is: Byte Multiplication Trick