In the previous post [see Elementary Cellular Automaton], I presented an implementation of a 1D elementary cellular automaton. Unfortunately, the code turned out to be an example of leaping into an idea without carefully reading the background information.

Long story short, while the code works and generates images, it doesn’t generate the correct images for all 256 rules. In this post, I present improved code that does.

I’m not here going to explain how cellular automata work. See the previous post for an explanation if needed. In this post, we’ll jump right into the problem with the first implementation and the changes that fix it.

To help get started (and because it’s needed by the code here), I will include the generate_rule function that gives us a rule dictionary given a rule number (an integer from 0 to 255, inclusive):

002|

003| def generate_rule (rule:int=110) -> dict:

004| ”’\

004| Generate a rule dictionary from a number.

004|

004| Arguments:

004| rule rule number (from 0 to 255)

004|

004| Returns:

004| dictionary of the eight rule conditions

004|

004| ”’

005| # Ensure we got a valid rule number…

006| assert type(rule) == int, ValueError(‘Rule number must be an integer.’)

007| assert 0 <= rule <= 255, ValueError(f’Invalid rule number: {rule}’)

008|

009| # Convert number to an eight-bit string…

010| sbits = f'{rule:08b}’

011|

012| # Convert bits string to a list of zeros and ones…

013| bits = [1 if b==‘1’ else 0 for b in sbits]

014|

015| # Generate and return the rule dictionary…

016| return {f'{bx:03b}’:b for bx,b in enumerate(reversed(bits))}

017|

018|

019| if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

020| rule = int(argv[1]) if 1 < len(argv) else 110

021|

022| rule_dict = generate_rule(rule)

023| for bx,bit_patt in enumerate(rule_dict):

024| print(f'{bx} [{bit_patt}]: {rule_dict[bit_patt]}’)

025| print()

026|

This is the same code from last time, so see the previous post for a detailed explanation. The short version is that the generate_rule function converts the integer to a list of the binary bits comprising the integer and builds a dictionary with three-bit keys indexing each bit.

As an aside, the design here uses three-bit string keys (like “000” or “011”), which requires the automaton to also generate three-bit string keys. An alternative design uses three-element tuple containing the raw 1 or 0 values — for instance, (0,0,0) or (0,1,1). Both techniques work. I went with string versions because I have a faint inherent mistrust of comparing tuples. This is just a mental twitch on my part; using tuples is not a problem and is arguably a cleaner approach (there are some cases where it can bite you, but those cases don’t apply here).

The error I made was making the initial row only long enough to contain the starting pattern of nonblank cells. In the default case, the initial row has just the one nonblank cell: [1]. To make life easier for the algorithm, I implemented the expand_row function to ensure three blank cells at the row start and end: [0,0,0,1,0,0,0].

From the beginning, I worried that the padding cells would introduce artifacts, because “000” is a valid triplet with a rule output. In the case of Rule 110, which was the use case I designed around, the output for “000” is 0, so no issue was apparent. It was only when I compared the outputs of all 256 rules to the examples shown in Wikipedia that I realized the code was broken. It turned out that my concern about artifacts was correct.

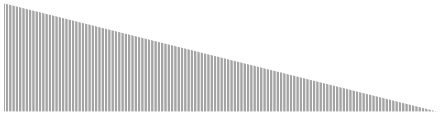

Any odd-numbered rule has output 1 for “000”, so using padding introduces artifacts for half the rules! In fact, Rule 1 outputs all zeros for all triplets except “000”. Which made the output for Rule 1:

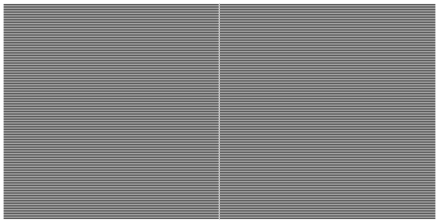

Which is incorrect (by a long shot). The output for Rule 1 should look like this:

(Click on any of these images for a full-sized version.) Obviously, the padding thing was a Bad Idea. And the problem jumped out immediately upon comparing my outputs with the Wikipedia versions.

Further, after closely reading the Wikipedia page, although it isn’t explicit about this, it became apparent that the initial row — and all rows thereafter — need to be the same size. For one thing, if we want an initial row populated with something other than the default single centered nonblank cell, it’s much handier to have a full-length row to populate.

This immediately raises the question of how long the initial row needs to be. I decided that, because some patterns create a 45° slope from the default single nonblank cell, the initial row should be twice as long as the number of rows generated by the automaton. A good example is the output for Rule 126:

The final row is twice the length of the number of rows because the pattern grows in both directions from center at respective 45° angles.

We already have a size parameter controlling the number of rows to generate, so we’ll use two times its value to determine the row length (which, again, applies to all rows generated). We no longer want padding (because of the artifacts), so we can discard the expand_row function and replace it with the initial_row function:

002|

003| def initial_row (size:int, start:list) -> list:

004| ”’\

004| Create an initial row that’s twice as wide as the number of iterations.

004| This allows the default start — a single centered nonblank cell — to

004| grow to the edge by the last row. That is, it allows a triangle from the

004| center top that grows to either or both edges at the bottom.

004|

004| Place the starting pattern in the center of the row (or use it as is

004| if it’s as long as twice the row count).

004|

004| Arguments:

004| size -number of rows requested

004| start -starting pattern

004|

004| Returns:

004| the intial row

004|

004| ”’

005| assert type(size) == int, ValueError(‘Row count must be an integer.’)

006| assert type(start) == list, ValueError(‘Start row must be a list.’)

007|

008| # Initial row must be twice the numbers of rows generated…

009| need = size * 2

010|

011| # If the starting row’s length is long enough, use it as is…

012| if need <= len(start):

013| return list(start)

014|

015| # Calculate amount of padding needed…

016| padding = (need – len(start)) // 2

017|

018| # Build the starting row…

019| row = ([0]*padding) + start + ([0]*padding)

020|

021| # Compensate for round-off…

022| while len(row) < need:

023| # This should happen only once (if at all)…

024| row.append(0)

025|

026| # Return the row…

027| return row

028|

029|

030| if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

031| size = int(argv[1]) if 1 < len(argv) else 100

032|

033| row = initial_row(size, [1])

034| print(“”.join(str(cell) for cell in row))

035| print()

036|

The function begins (lines #5 and #6) by validating its inputs, size and start. Then it calculates how long the initial row needs to be (line #9). If the start parameter holds a list at least that long, we just return it (lines #12 and #13).

Otherwise, we calculate the padding necessary on each side to extend the list to the row length needed (line #16). The idea is that, if the start pattern is shorter than the row length, it will be centered in the row. Line #19 creates the initial row.

Finally (lines #21 to #24), we ensure the initial row is the correct length, because the round-off from the integer division in line #16 might leave it one cell short. I used a while loop to guarantee the final result is the correct length, but it should never be necessary to actually repeat the loop (assuming it happens even once).

Line #27 returns the created initial row. Note this is distinctly different from the expand_row function, which modified an existing row.

The code on lines #30 through #35 exercise the function.

With the generate_rule and initial_functions defined, we can move on to the run_automaton function:

002| from os import path

003| from examples import generate_rule, initial_row

004|

005| def run_automaton (rule, size, start=[1], fname=‘automaton.out’, fpath=”):

006| ”’\

006| Elementary cellular automata (per almost every CS course ever).

006| See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elementary_cellular_automaton

006|

006| Arguments:

006| rule rule number, from 0 to 255

006| size number of iterations

006| start the initial row, typically just [1]

006| fname filename for the text output (use None to use stdout)

006| fpath filepath or None if fname is a full path/filename

006|

006| Returns:

006| list of size+1 generated rows (includes initial row)

006|

006| ”’

007| print(f’Run automata with rule {rule} ({size} rows)’)

008| print()

009| make_key = lambda xs: ”.join(str(x) for x in xs)

010|

011| # Create the initial row…

012| row = initial_row(size, start)

013|

014| # Generated rows appended to this list…

015| rows = [row]

016|

017| # Get the rule for this run…

018| current_rule = generate_rule(rule)

019|

020| # Iterations of rule…

021| for rx in range(size):

022| # Create new row of all blanks…

023| new_row = [0]*len(row)

024|

025| # For each triplet in the current row…

026| for ix in range(len(row)):

027|

028| # Convert the triplet to a key…

029| if ix == 0:

030| # Edge case: first triplet extends beyond start of row…

031| key = make_key(row[0:1] + row[0:2])

032| elif ix == len(row)–1:

033| # Edge case: last triplet extends beyond end of row…

034| key = make_key(row[ix–1:ix+1] + row[ix:ix+1])

035| else:

036| # The usual case…

037| key = make_key(row[ix–1:ix+2])

038|

039| # Get the value per the rule…

040| val = current_rule[key]

041|

042| # And put it in the new row…

043| new_row[ix] = val

044|

045| # Make the new row the current row…

046| row = new_row

047|

048| # Append the (new) row to the output list…

049| rows.append(row)

050|

051| # We’ll default to the display…

052| sout = stdout

053| # But if a filename is supplied, open a file…

054| if fname:

055| # Include the rule ID in the filename (optional)…

056| if ‘%s’ in fname:

057| fname = fname % f'{rule:03d}’

058|

059| filename = path.join(fpath,fname) if fpath else fname

060| sout = open(filename, mode=‘w’, encoding=‘utf8’)

061|

062| # For the display, convert 0s and 1s to something printable…

063| output = [”.join(‘#’ if c else ‘ ‘ for c in row) for row in rows]

064|

065| # Display (or write to file) the output…

066| try:

067| for line in output:

068| print(line, file=sout)

069|

070| except:

071| raise

072|

073| finally:

074| if fname:

075| sout.close()

076| print(f’wrote: {filename}’)

077| print()

078|

079| # Return the list of generated rows…

080| return rows

081|

082|

083| if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

084| rule = int(argv[1]) if 1 < len(argv) else 110

085| size = int(argv[2]) if 2 < len(argv) else 200

086|

087| rows = run_automaton(rule, size, fpath=r’C:\demo\hcc\python’)

088|

This is essentially the same function as we used last time with only a handful of changes. The first change is that line #12 now calls the initial_row function rather than the expand_row function. Also, in line #46, we formerly passed the new row through the expand_row function to ensure padding, but now we can just assign new_row to row.

The bigger change involves lines #28 through #37. In the old version (because we knew there was always padding), we simply grabbed triplets to use as keys, which took only one line of code (line #32 in the old code). Now, because there is no padding and we want to put a rule output value into every cell of the new row, we need to compensate for two special cases where the triplet hangs off the edge of the row by one cell. (Remember, the center cell of the triplet is where the new value goes.)

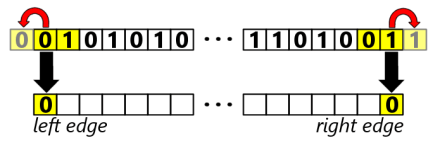

Here’s an illustration of the requirement:

The faded cells in the above represent a “virtual” cell (that isn’t really there) on each end of the row. We duplicate the triplet center cell — whatever it is — as that virtual cell. Lines #29 to #31 handle the left-hand case, and lines #32 to #34 handle the right-hand case.

Other than these two changes, the code is the same as the old version. Lines #83 to #87 exercise the function.

For completeness — and to correct a minor bug from the old version — here again is the code that converts the generated row data into an image file:

002| from os import path

003| from PIL import Image, ImageDraw, ImageFont

004| from examples import run_automaton

005|

006| ImageBackground = (255,255,255)

007| ImageForeground = (0,0,0)

008|

009| NumberImage = False

010| NumberSize = 18

011| NumberColor = (255,0,0)

012| NumberFont = ‘arialbd.ttf’

013|

014| def make_automaton_bitmap (rule, rows, margin, fname=‘automaton.png’, fpath=”):

015| ”’\

015| Generate a PNG file from the automata output.

015|

015| Arguments:

015| rule the rule number (for the filename)

015| rows output from the automata

015| margin width of image border (in pixels)

015| fname filename for the image file (required)

015| fpath filepath or None if fname is a full path/filename

015|

015| Returns:

015| nothing (None)

015|

015| ”’

016| bg_color = ImageBackground # background (nominally white)

017| fg_color = ImageForeground # cells (nominally black)

018|

019| # Image width is the longest row plus margins…

020| width = len(rows[–1]) + (2 * margin)

021| # Image height is the number of rows plus margins…

022| height = len(rows) + (2 * margin)

023|

024| # Create a new image…

025| img = Image.new(‘RGB’, size=(width,height), color=bg_color)

026| # And a drawing object…

027| draw = ImageDraw.Draw(img)

028|

029| # For each row of output…

030| for rx,row in enumerate(rows):

031|

032| # For each cell in the row…

033| for cx,cell in enumerate(row):

034| # Draw one pixel if cell is nonblank…

035| if cell:

036| px = cx + margin

037| py = rx + margin

038| draw.point((px, py), fill=fg_color)

039|

040| # Place rule number in upper-left corner (optional)…

041| if NumberImage:

042| fnt = ImageFont.truetype(NumberFont, size=NumberSize)

043| draw.text((0,0), str(rule), font=fnt, fill=NumberColor)

044|

045| # Include the rule ID in the filename (optional)…

046| if ‘%s’ in fname:

047| fname = fname % f'{rule:03d}’

048|

049| # We want a complete filename for the image…

050| filename = path.join(fpath,fname) if fpath else fname

051|

052| # Save the image…

053| img.save(filename)

054| print(f’wrote: {filename}’)

055| print()

056|

057|

058| if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

059| rule = int(argv[1]) if 1 < len(argv) else 110

060| size = int(argv[2]) if 2 < len(argv) else 400

061|

062| # Run the automaton…

063| rows = run_automaton(rule, size, fpath=r’C:\demo\hcc\python’)

064|

065| # Generate an image file…

066| make_automaton_bitmap(rule, rows, fpath=r’C:\demo\hcc\python’)

067|

There are a few minor changes. Firstly, lines#6 to #12 define some global constants the make_automata_bitmap function uses. The first two specify the background and foreground color (the old code had the constants in the code — a coding no-no).

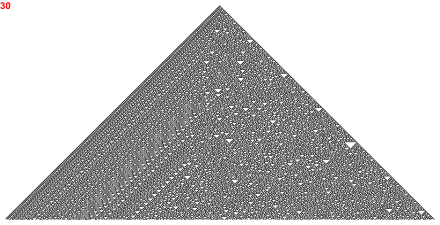

The four NumberXxxx constants determine whether the output image has the rule number in the upper-left corner. They also specify the size, color, and font of the superimposed number. The code already allows for output files (both the text and image) to include the number in the filename. When enabled, the image looks like this:

Now the image self-identifies as Rule 30 (one of the more interesting rules besides Rule 110).

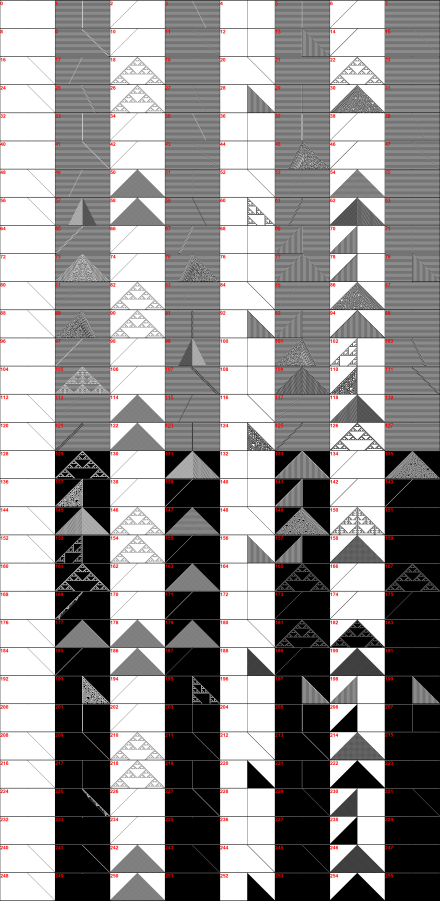

I wanted the image to include the rule number as part of the all-256-rules “catalog” image I created as a reference:

The catalog (click for big) shows all 256 rules, and the eight-column format highlights the commonality of rules. For instance, odd-numbered rules have darker backgrounds, largely because the output of a “000” triplet is a 1.

One thing I found interesting is the prevalence of Sierpiński triangles generated by a number of rules. Upon reflection, it makes sense given how this automaton works, but it surprised me at first (note the bigger version above from Rule 126).

And that’s about it for this time.

Link: Zip file containing all code fragments used in this post.

∅

ATTENTION: The WordPress Reader strips the style information from posts, which can destroy certain important formatting elements. If you’re reading this in the Reader, I highly recommend (and urge) you to [A] stop using the Reader and [B] always read blog posts on their website.

This post is: Cellular Automaton Redux

Pingback: Elementary Cellular Automaton | The Hard-Core Coder